1

/

of

7

so-en ∙ nov 1 1980

so-en ∙ nov 1 1980

y's

Regular price

1 CAD

Regular price

Sale price

1 CAD

Unit price

/

per

description

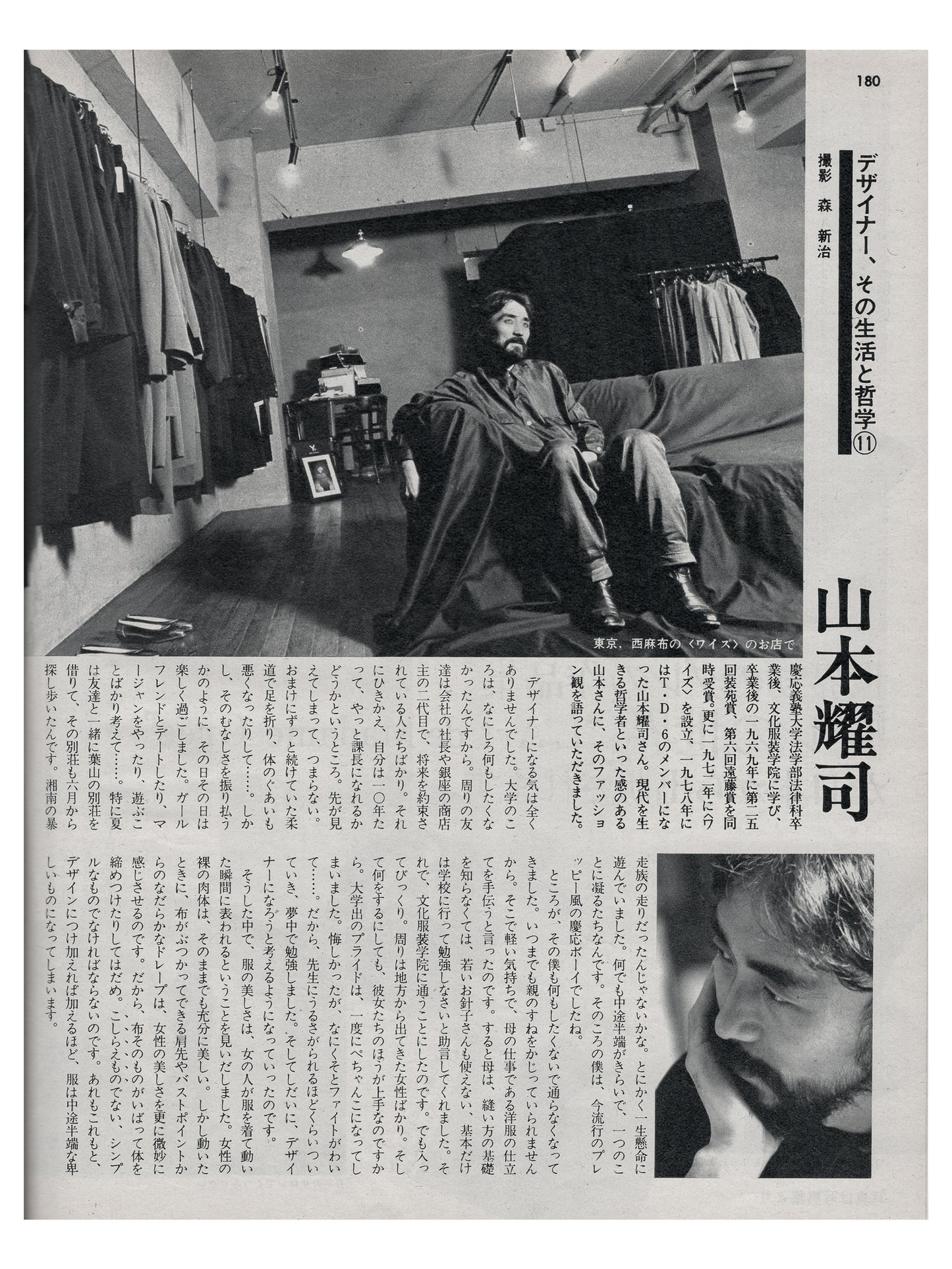

yohji yamamoto captured in his late '30s during the early days of his success in the domestic market. here he is seen in an early studio / showroom space, reflecting upon the philosophy behind his craft - words which may be even more relevant today, some 45 years later.

additional feature on autumn / winter styles with outfits selected by yohji and rei, complete with patternmaking instructions and diagrams. published by bunka's publishing bureau, so-en had a strong foundation as a dressmaking magazine while some of its sister publications were more trend or style focused.

notes

published by bunka publishing bureau

softcover ∙ 20.5 x 26 cm ∙ 7 pp

Designers, Their Lives and Philosophies #11: Yamamoto Yohji

At the Y's store in Nishi-Azabu

After graduating from the Faculty of Law at Keio University, Yohji Yamamoto studied at Bunka Fashion College. In 1969, he simultaneously won the 25th Soen Prize and the 6th Endo Prize. Later, in 1972, he established Y’s, and by 1978, he became a member of T.D.6. Often seen as a modern-day philosopher, Yamamoto shared his perspective on fashion with us.

I had absolutely no intention of becoming a designer

Back in university, I really didn’t want to do anything at all. My friends were all sons of company presidents or second-generation shop owners in Ginza, people with secure futures. In contrast, I saw myself struggling for ten years just to maybe become a senior manager. The future seemed so predictable and dull.

On top of that, I broke my leg in judo, which I had been practicing for years, and my health started to decline. But in an attempt to shake off that emptiness, I focused on enjoying each day — dating girlfriends, playing mahjong, and just having fun. Especially in the summer, my friends and I would rent a villa in Hayama, searching for one as early as June. We were probably the early version of youth motorcycle gangs. In any case, I played hard. I’ve always hated doing things halfway — when I get into something, I get obsessed. At that time, I was a typical Keio Boy, dressed in the preppy style that’s trendy now.

But eventually, I couldn’t keep up my "I don't want to do anything" attitude. I couldn’t live off my mother forever. So, without much thought, I told her I’d help with her dressmaking business. She told me that if I didn’t know the basics of sewing, I wouldn’t even be able to manage young seamstresses. She advised me to at least learn the fundamentals at school.

That’s how I ended up at Bunka Fashion College, and I was shocked. The school was full of women from rural areas, and they were all better at sewing than I was. My pride as a university graduate was instantly crushed. It was frustrating, but I refused to back down. I studied so hard that even my teachers found me annoying. Before I knew it, I was thinking seriously about becoming a designer.

Through this experience, I realized that the beauty of clothing reveals itself in the moment a woman moves in it. A woman’s bare body is already beautiful, but when she moves, the fabric meets her skin, creating gentle drapes from her shoulders or bust — these subtle details enhance her beauty even further.

That’s why fabric shouldn’t dominate or constrict the body. Clothing shouldn’t feel artificial — it should be simple. The more you add to a design, the more it becomes overworked and loses its integrity.

The most important thing when I create clothing is comfort

For the person wearing it, the garment should have meaning — it should align with their spirit and way of life. In fashion, the wearer's essence is the most crucial element, making up at least 60% of the whole. The designer’s role, in contrast, is only about 20-30%. That’s why my clothes are never fully complete. They are meant to be finished by the person who wears them.

The kind of person I want to wear my designs is strong, clear in their intentions, and self-sufficient — someone who has built their own life. I want my clothes to be worn by women who have their own work, who have decisively moved forward in life, and who possess a certain human depth. To these women, I want to dedicate my utmost effort and sincerity in crafting garments.

If someone chooses to spend their hard-earned money on Y's, I want to be worthy of that choice. It might sound monastic, but isn’t that what a designer brand should be? Unlike mass apparel, which is created based on marketing data and trend analysis, a designer brand is an expression of the designer’s direct experiences in life. That’s why I must constantly refine myself and maintain a tense, meaningful relationship with the people who wear my clothes — otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to create pieces that are truly alive with energy and intent.

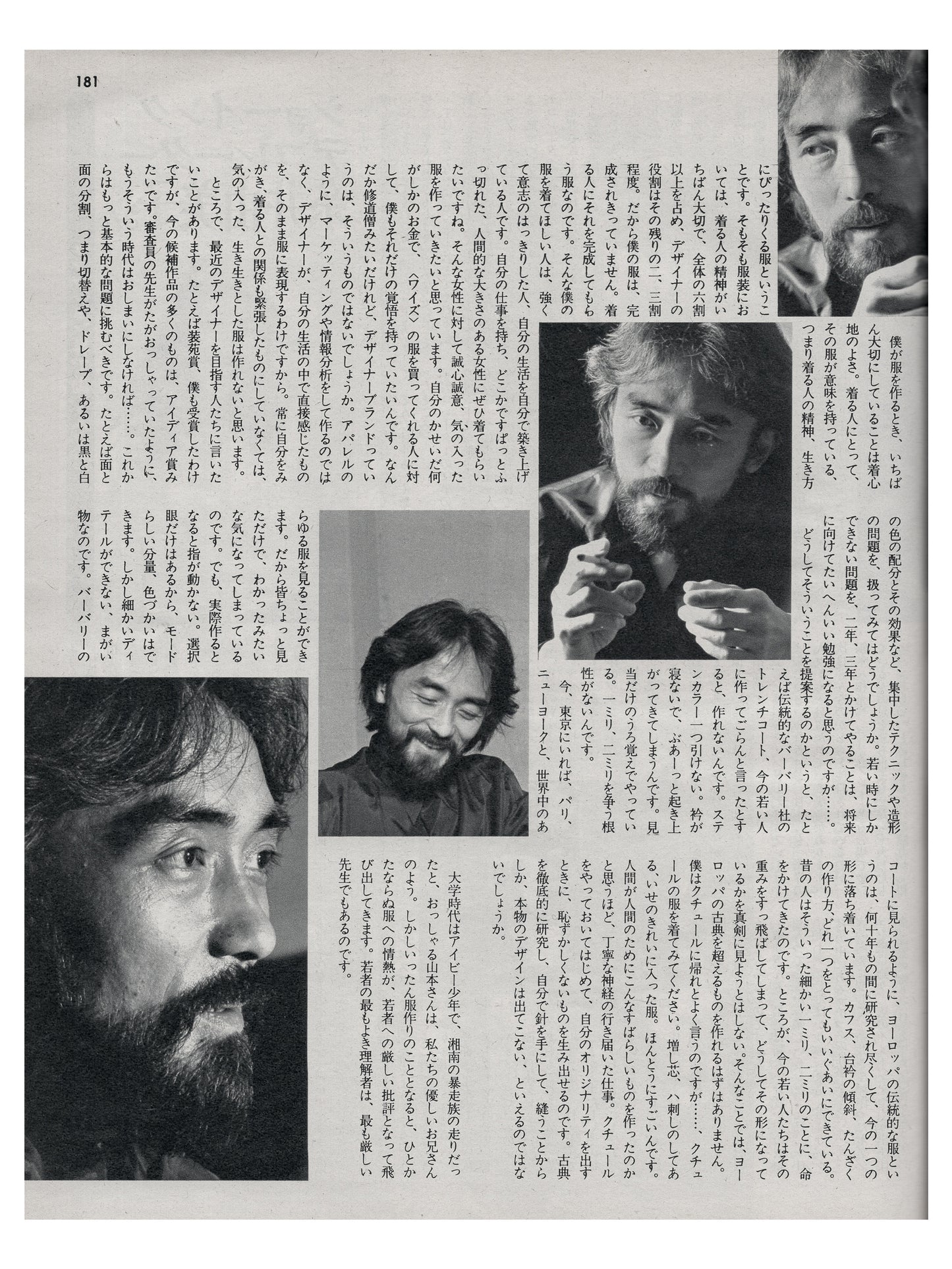

A message to aspiring designers

There’s something I want to say to those aiming to become designers today. Take the Soen Award, for example — I won it myself — but many of today’s entries feel more like "idea awards." As the judges have mentioned, it’s time to move past that era.

From now on, young designers should tackle more fundamental challenges — things like fabric paneling and seam placement, draping techniques, or the effects of black-and-white color balance. These are serious issues of form and technique, and dedicating two or three years to mastering them would be an incredibly valuable learning experience for the future.

Why do I suggest this? Because if you ask a young designer today to recreate a classic Burberry trench coat, most wouldn’t be able to do it. They wouldn’t even be able to draft a simple balmacaan collar — the collar would stick up stiffly instead of lying flat. They’re working from vague memories rather than true understanding.

Right now, in Tokyo, you can see fashion from Paris, New York, and all over the world. Because of that, many designers think they understand something just by looking at it. But when it comes to actually making it, their hands don’t know what to do. They may have a good eye for trends, silhouettes, and color balance, but they lack attention to fine detail. What they end up creating are counterfeits, not true craftsmanship.

As seen in Burberry coats, traditional European clothing has been meticulously studied for decades, ultimately settling into its current form. Every detail, from the angle of the collar stand to the construction of cuffs and plackets, has been perfected. The craftsmen of the past dedicated themselves to these millimeter-level refinements.

However, young designers today tend to overlook this weight of tradition. They fail to seriously examine why these designs have taken their current form. Without understanding that foundation, how can they ever hope to create something that surpasses classical European designs?

I often say, "Return to couture." Try wearing a couture garment. Experience the reinforced interlining, the fine hand-stitching, the beautifully eased seams. It's truly remarkable. The level of meticulous craftsmanship is so extraordinary that you might wonder how humans could create something so exquisite.

Only by mastering couture can one produce original designs that are not embarrassing to present. True design does not emerge unless you thoroughly study classical techniques, take a needle in hand, and sew for yourself.

Yamamoto, who describes himself as an Ivy League-style youth and an early member of the youth biker scene during his university days, comes across as an older brother figure to us. However, when it comes to fashion design, his deep passion for clothing transforms into sharp critiques of young designers. The best mentor for young creatives is often the toughest teacher.

SO-EN Special Selection - 20 Autumn Suits Recommended by 10 Designers

This season, we asked 10 designers to each create two suits, bringing you a curated selection of 20 unique, expressive outfits. Enjoy the individuality of each suit and the styling that brings them to life. ★ Dresses marked with a star will be given away to readers. For details, check the reader’s card.

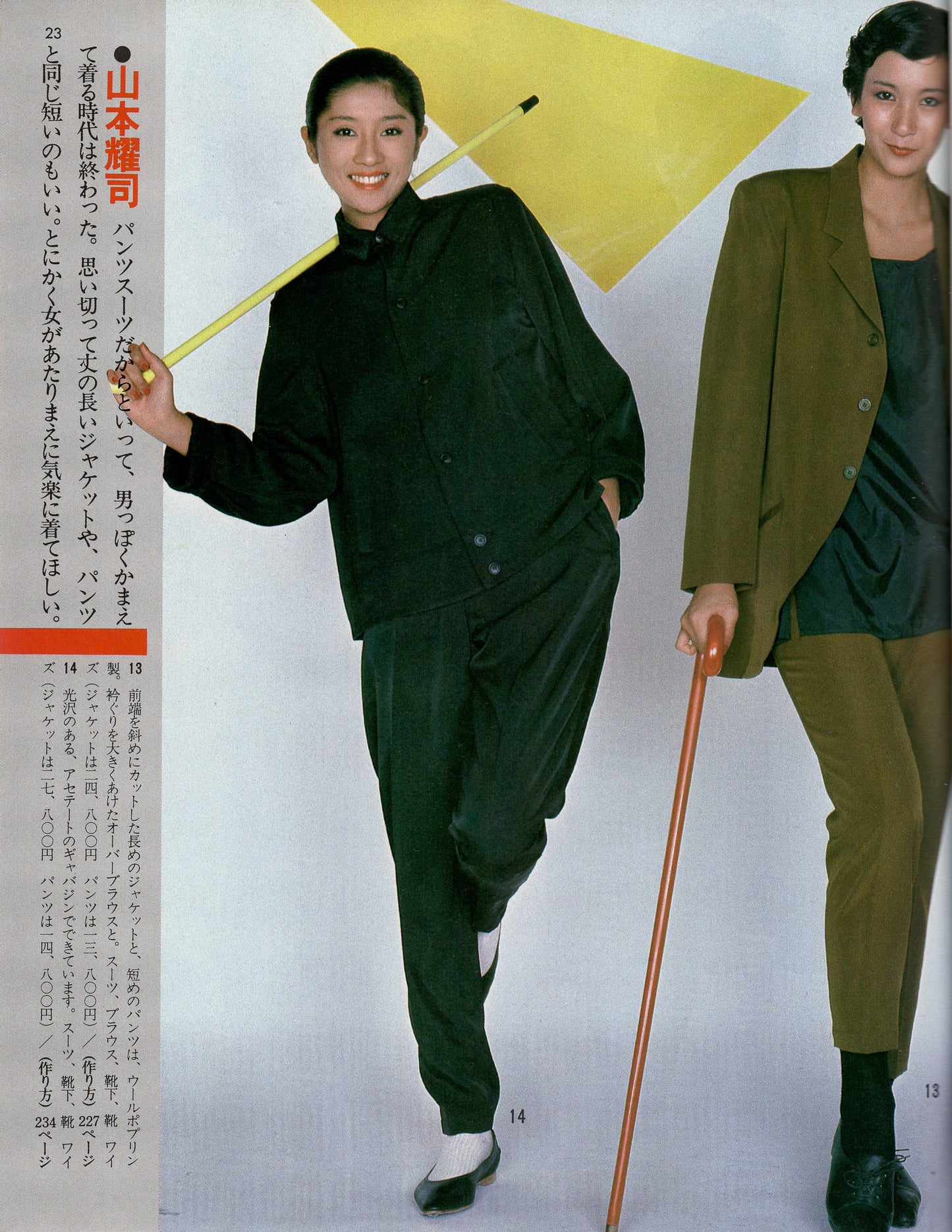

Yamamoto Yohji

Just because it's a pantsuit doesn't mean women need to wear it with a masculine attitude anymore. Those days are over. Boldly wearing a long jacket — or even a short one that matches the pants — is great too. The point is, I want women to wear pantsuits naturally and comfortably, like it's the most ordinary thing in the world.

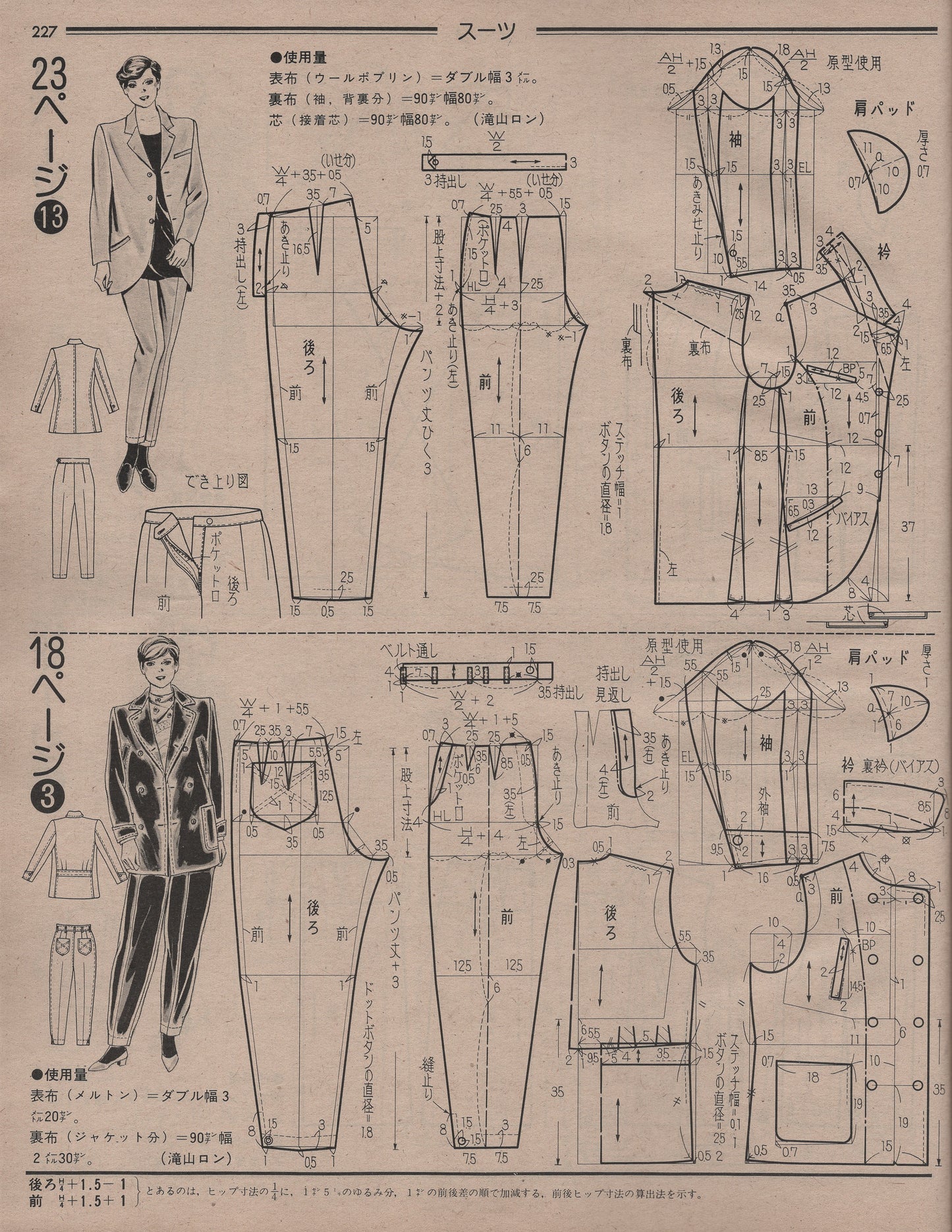

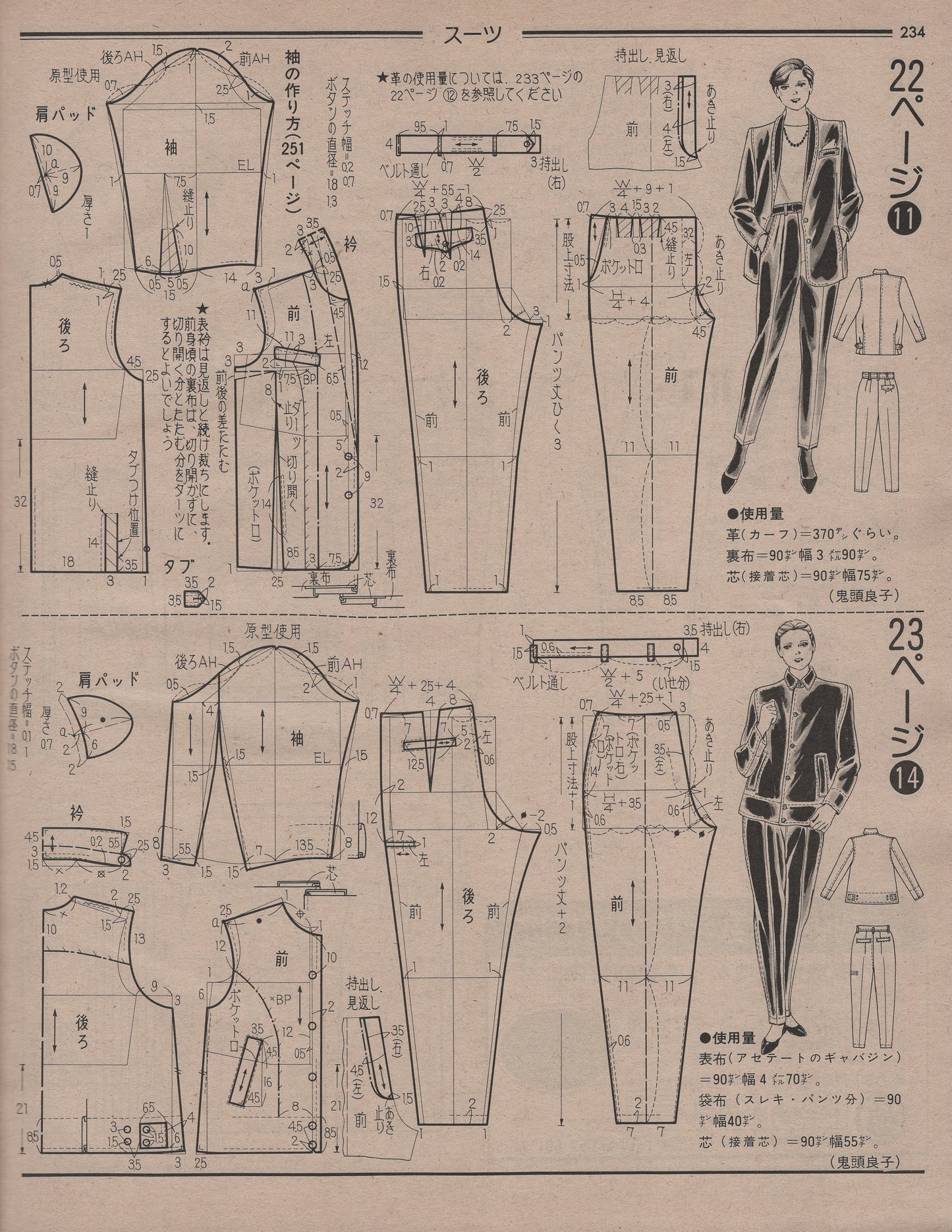

13 A long jacket with a diagonally cut front hem paired with short pants, both made of wool poplin. Worn with an overblouse featuring a wide neckline. Suit, blouse, socks, and shoes by Y’s (Jacket: ¥24,800 / Pants: ¥13,800) (How to make it – see page 227)

14 Made of glossy acetate gabardine. Suit, socks, and shoes by Y’s (Jacket: ¥27,800 / Pants: ¥14,800) (How to make it – see page 234)

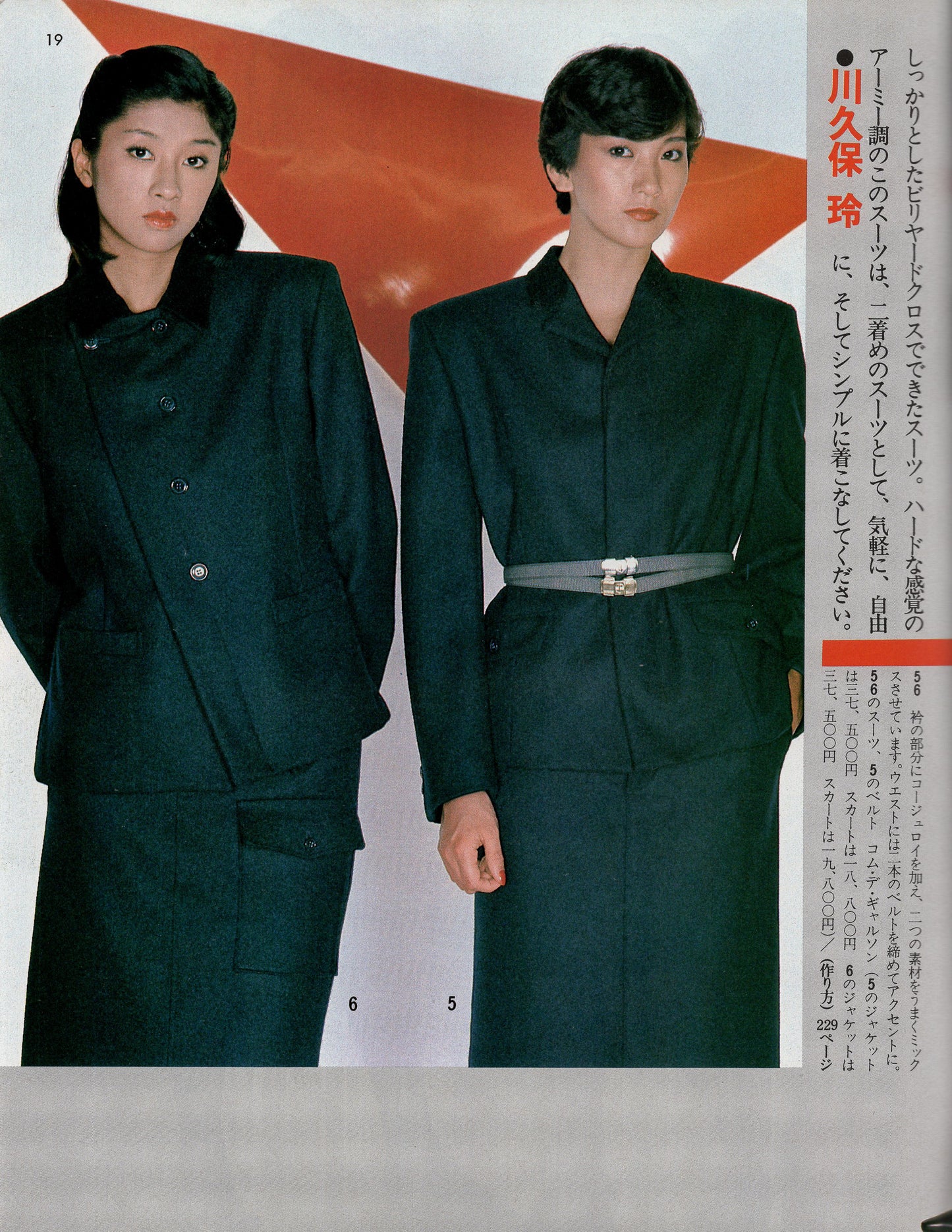

Kawakubo Rei

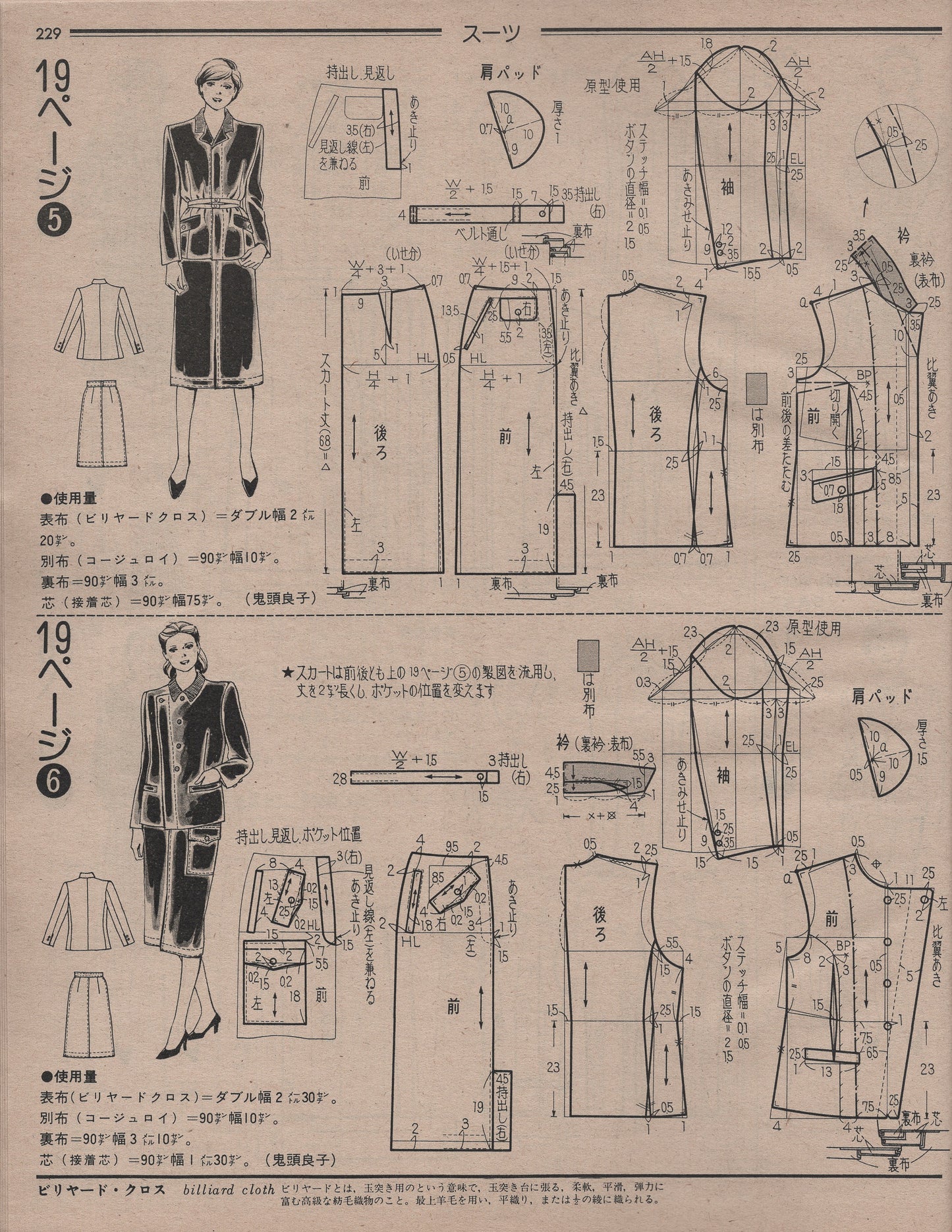

A suit made from sturdy billiard cloth. With its tough, military-inspired feel, this suit is perfect as a second option — wear it with ease, freedom, and simplicity.

5 & 6 The collar features added corduroy, skillfully mixing two different materials. Two belts are cinched at the waist for a striking accent. Suit from 5 & 6, belts from 5 — Comme des Garçons (No.5 - Jacket: ¥37,500 / Skirt: ¥18,800, No.6 - Jacket: ¥37,500 / Skirt: ¥19,800) (Jacket 5 & 6 - How to make it - see page 229)