1

/

of

6

sankei ∙ jul 1982

sankei ∙ jul 1982

yohji yamamoto

Regular price

1 CAD

Regular price

Sale price

1 CAD

Unit price

/

per

description

Longform interview following the A/W '82 collection. Valuable insight regarding his Paris breakthrough as well as ideas of sucess, beauty, and material posessions.

notes

published by sankei shimbun co. ltd.

softcover ∙ 18 x 25.5 cm ∙ 4 pp

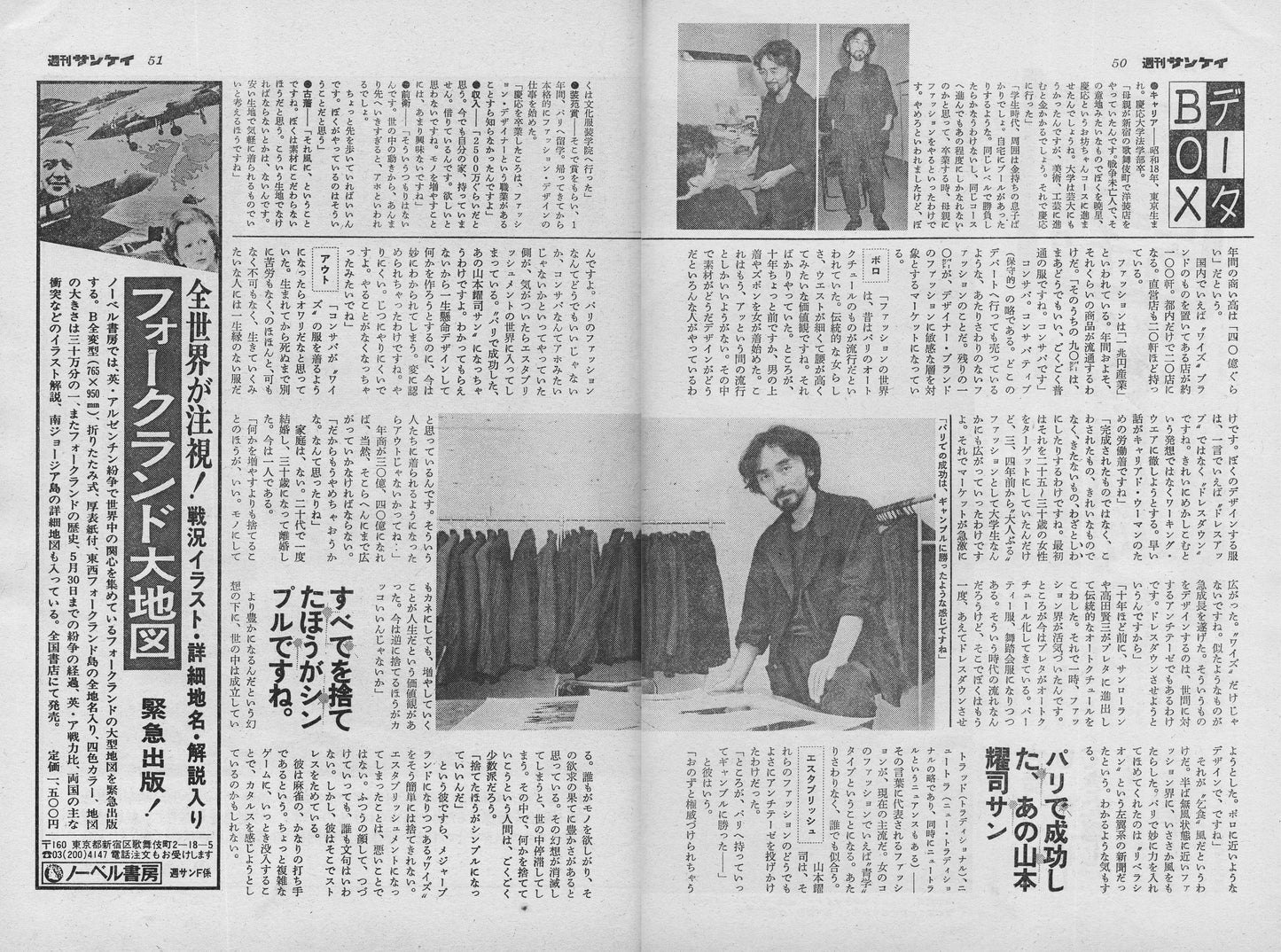

A fashion designer who rose to success through vintage clothing: Yohji Yamamoto

PARIS — Why is it that people say 'this city is the center of fashion' — New York, London, Tokyo — saying that it's no longer Paris' era… yet when it comes down to it, industry insiders still fly to Paris?

In Paris, large-scale shows are held twice a year, and because it’s customary for Japanese newspapers to at least cover them during those periods, this is relatively well known. In the fall, collections for the following year's spring and summer are presented, while in the spring, fall and winter collections are showcased. The time and place for the shows are strictly divided between haute couture (custom clothing) and prêt-à-porter (luxury ready-to-wear). In recent years, it is the prêt-à-porter side that has been gaining vitality.

If the fashion show is considered the public stage, then business transactions take place behind the scenes. Buyers who come from various countries view the products and make design contracts on the spot. Many designers have debuted from within such staged environments. Kenzo Takada, Issey Miyake, Hanae Mori… those names you've likely heard often are all designers who, in some form, had their moment in the spotlight on the Paris stage. Last fall and again this spring, there was a designer who participated in the prêt-à-porter shows twice in a row. His name is Yohji Yamamoto (38). "As for the results — well, I suppose you could call it a success," he says.

SUCCESS — “There are hundreds of fashion journalists who see the work of various designers and write all sorts of articles about them. Some journalists evaluated my work favorably, and I received a considerable number of orders from buyers in New York, London, Italy, and Paris.”

Generally speaking, that would be called a success. About half a year ago — Yohji Yamamoto, having gained recognition in Paris, held an outdoor fashion show at Tokyo’s Denen Coliseum. “It was an incredibly cold day, but around 8,000 people showed up, mostly young people. I couldn’t help but wonder — what was going on?”

There too, once again, he found success. Most designers, having achieved something like that, would boast about it — after all, it's like obtaining a ticket to live and work in this industry. It wouldn’t be strange to show it off. But Yohji Yamamoto doesn’t go on and on about his success in Paris.

“I don’t think that simply going out to show in Paris prêt-à-porter is all that difficult. As long as you have the career and organization that prove you are a designer who can continue steadily, and since there is a prêt-à-porter association, it’s enough if you can pay the membership fee to join. The prêt-à-porter shows are the shows of that association’s members. It’s not as if I felt I absolutely had to do it in Paris. If anything, I thought, ‘Paris doesn’t really matter, does it?’ Then why did I go out to Paris?”

“One reason is that I wanted to export. It’s interesting, isn’t it? The clothes I make are, if you put it bluntly, like beggar’s clothes (laughs). If something like that could be exported, there’d be nothing more interesting.” Clothes like a beggar’s. Before explaining that, he has one more reason for having gone out to Paris. “If you do it in Paris and get ignored, you’re finished, right? They’ll say, ‘You fool,’ and that’s the end of it. If you succeed, on the contrary, everything goes well. It’s like a gamble. And that too is interesting, isn’t it? Stimulating.”

'SERVES YOU RIGHT' — What’s good is that it isn’t a fashionable motive. “Since that’s the feeling with which I went out there, having succeeded, the feeling now is something like, ‘Serves you right,’ I suppose.” he says.

FOUR BILLION — The clothes designed by Yohji Yamamoto carry the brand name Y’s. Originally, it was a women’s brand. Now it has broadened its scope with Y’s for Men and Workshop (casual wear), and its annual business turnover is said to be around four billion (yen). In Japan, there are about one hundred shops that carry the Y’s brand. In Tokyo alone, that comes to twenty shops. They also have around twenty directly managed stores.

Fashion is said to be a one-trillion-yen industry. Each year, roughly that amount of goods circulates. ‘About ninety percent of that is — well, whatever — extremely ordinary clothing. Consaba. It is the abbreviation of conservative (meaning ‘traditional’). It refers to unremarkable fashion — the kind sold at any department store, with nothing that stands out. The remaining ten percent becomes the market aimed at the segment that is sensitive to designer-brand fashion.

BORO — “In the fashion world, it used to be said that what was in vogue was the Paris haute couture. A traditional sense of femininity — like having a narrow waist and high hips. They did nothing but that. But then, was it a little over ten years ago, women began wearing men’s jackets and trousers. This can only be described as a trend that spread in the blink of an eye. Within that, various people are doing things — saying the material should be this, the design should be that. The clothes I design, in a word, are not dress-up but dress-down. Rather than the idea of making yourself look beautiful and all done-up, I try to commit fully to working wear. To put it plainly, they’re work clothes for career women.”

“Not something completed, but something broken; not something beautiful, but something dirty — I intentionally put wrinkles in it and such. At first, I was targeting women aged twenty-five to thirty, but from three or four years ago, it spread even to university students as a fashion for ‘acting grown-up.’ And so the market expanded rapidly. It wasn’t only Y’s. Similar kinds of things experienced rapid growth. Designing such things is, in a sense, an antithesis toward society. Since what we are trying to do is make people dress down.”

“About ten years ago, Saint Laurent and Kenzo Takada moved into prêt-à-porter and broke apart the traditional haute couture. Because of that, for a time, the fashion world became lively. But now prêt-à-porter is becoming like haute couture. It is turning into party wear, ballroom wear. It’s probably the flow of the times, but there, I deliberately tried once more to make things dress down.”

With designs close to boro, yes. That is what he means by “beggar-style.” In a fashion world that was in a state close to windlessness, he brought in a bit of wind, and the one that praised him with curious intensity in Paris was the left-wing newspaper Libération. I feel like I can understand why.

Trad (traditional), New-Tra (short for new traditional, and at the same time carrying a nuance of ‘neutral’) — the fashion represented by those words is the current mainstream. Speaking in terms of girls’ fashion, it would be the ‘Aoyama Gakuin type.’ Unobjectionable, suits anyone.”

ESTABLISHMENT — Yohji Yamamoto threw an antithesis at the triviality of those fashions. "But then, I took it to Paris and won the gamble", he says. “You end up being endowed with authority, inevitably. The side that was saying, ‘Paris fashion doesn’t matter,’ or ‘Conservative fashion is ridiculous,’ before you know it, finds itself entering the world of the establishment. You become the 'Mr. Yohji Yamamoto who succeeded in Paris'. "Even though you work so hard to design and try to create something because people don’t understand you, now they strangely understand you. I’ve been recognized in some odd way. It’s difficult. Truly difficult. It feels as if I’ve run out of things to do.”

OUT — “I had always thought that it would be the end once conservatives started wearing Y’s clothes without any struggle, just easy going, with nothing particularly good or bad about it. I believe these clothes have no connection whatsoever, for an entire lifetime, to people who live from birth to death in a way that is neither good nor bad. If it reached the point where those kinds of people started wearing them, wouldn’t that be 'out', you know…?” When annual sales reach three or four billion, naturally, it has to spread even into those areas.”

“So I sometimes think, maybe I should just quit already.” He has no family. He married once in his twenties and divorced when he turned thirty. He is alone now. “Rather than increasing something, throwing things away is better. There was a value system that said life was about piling up things or money. Now, on the contrary, isn’t throwing things away the cooler way?” The world is built upon the illusion that we become richer. Everyone wants things, and they believe that at the end of that desire lies abundance. If that illusion were to disappear, the world would come to a standstill. Within that, people who try to throw things away are surely an exceedingly small minority.

“It’s better to throw things away — it becomes simpler", he says. And yet even he cannot so easily throw away Y’s, which is on its way to becoming a major brand. Becoming part of the establishment is not a bad thing. Even if he were to continue on with an ordinary face, no one would complain. But he is accumulating stress there.

He is said to be quite a skilled mah-jong player. By immersing himself for a time in a somewhat complex game, he may be trying to feel a kind of catharsis.

“The success in Paris feels like having won a gamble.”

Career — Born in Tokyo in 1943 (Shōwa 18). Graduated from Keio University, Faculty of Law.

“My mother ran a Western-clothing shop in Shinjuku’s Kabukichō. She was a war widow, and out of something like her pride, she pushed me along the rich-boy course — Gyosei, then Keio. I also passed the entrance exam for Geidai (Tokyo University of the Arts), but going into art or crafts costs money, right? So I went to Keio. As a student, everyone around me was the son of a rich family. The kind who have a pool at home. If I tried to compete on that level, there’s no way I could win, and if I followed the same course as them, I felt I’d only ever become that much at best. So when I graduated, I told my mother I was going into fashion. She told me to stop, but I went to Bunka Fashion College.”

Sōen Prize — After receiving the prize, he studied in Paris for a year. After returning to Japan, he began working in fashion design in earnest.

“When I graduated from Keio, I didn’t even know the profession ‘fashion designer’ existed.”

Income — “I think it’s around 25 million yen. Even now, I don’t own my own home. I rent. I don’t feel like wanting one. I’m not very interested in accumulating things.”

Avant-garde — “I don’t have such intentions. If you go too far ahead of the movement of the world, people will call you an idiot, right? Walking just a little ahead is enough. I think what I’m doing is something like that.”

Old clothes — “It’s that sort of feeling, you know. I think I’m someone who doesn’t fuss over materials. I’m not the type who says, ‘It has to be this fabric.’ I lean toward thinking it’s fine if it’s affordable fabric you can wear casually.”